Over the past four years I have been focused on designing digital courses (self-paced, asynchronous eLearning) in the customer education space. Through continual iterations and gathering of customer feedback, I have finally discovered and am excited to share an effective instructional design framework for architecting relevant and impactful digital learning experiences.

It’s important to emphasize that improving human performance is a continuous process and digital courses are only one part of the solution. To successfully achieve organization goals and metrics, it is vital that we also discover and improve human and environmental gaps related to the target audience’s culture, processes, technologies, incentives, and more.

This article is organized into the following sections:

- The framework

- An example course outline

- Levels of instruction

- Indicators of good instruction

- Guidelines to keep in mind

- Conclusion

- References

The framework

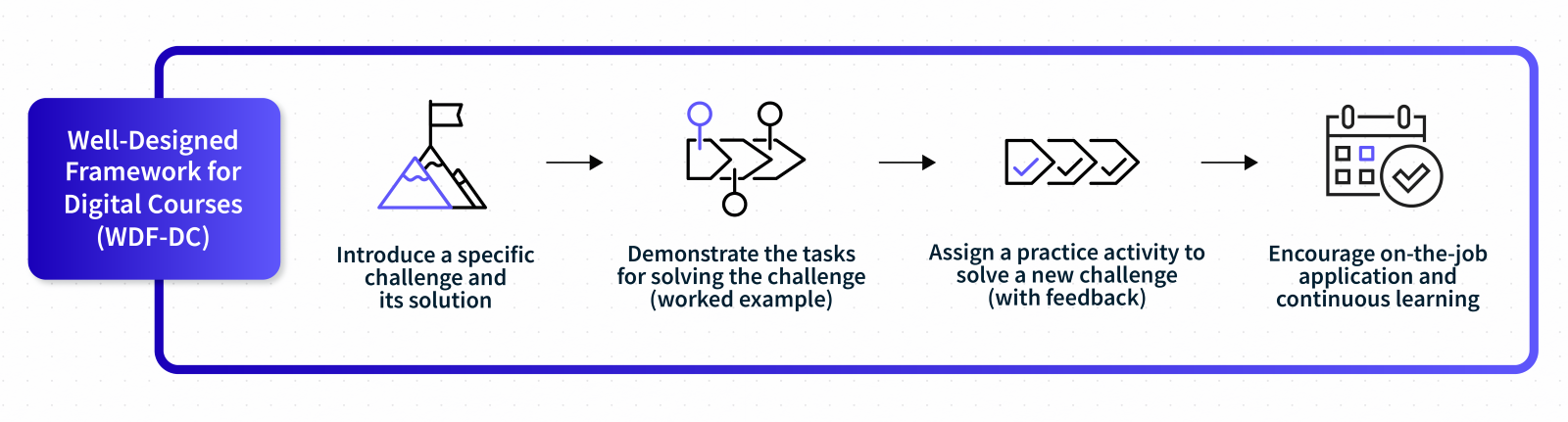

The Well-Designed Framework for Digital Courses (WDF-DC) is an evidence-informed instructional approach for architecting highly relevant, skill-transforming, and scalable digital learning experiences. The framework consists of a series of four key instructional events. (Figure 1 and Table 1)

Figure 1. The Well-Designed Framework for Digital Courses (WDF-DC)

Table 1. Instructional Events in the Well-Designed Framework for Digital Courses

| Instructional Event | Description |

| Introduce a specific challenge and its solution | First, introduce a realistic and relevant challenge. The purpose of this challenge is to hook or grab the attention of the learner, activate their prior knowledge, and set a single-threaded narrative for the entire learning experience. Second, introduce the solution via a short description and a visual diagram. This helps learners organize and construct a clear mental model of the whole solution and its parts. Third, describe the value or benefits of implementing the solution. This helps clarify the "why" or what’s in it for me (WIIFM), so they can start caring about the "how". |

| Demonstrate the tasks for solving the challenge (worked example) | Provide a worked example or the step-by-step tasks for solving the challenge. The demonstration can be a video tutorial, a user guide, or both. When learners observe an expert walking through a worked example, especially with explanations for their decisions, it creates a practical and tangible learning experience. |

| Assign a practice activity to solve a new challenge (with feedback) | Introduce a new challenge and assign a practice activity for solving it. The new challenge needs to be similar to the original challenge but with some variations to ensure critical thinking. It is essential that learners receive feedback to help them identify gaps in their individual performance. For technical domains, you can provide a simulation or lab environment for practice and feedback. For non-technical domains, you can create decision-making activities (branching scenarios) or request assignment submissions for expert review and feedback. If creating a practice activity is not possible or feasible, then at a minimum request the learner to practice on their own by following along with the demonstration. For simple tasks, Ruth C. Clark suggests that demonstrations can be sufficient for learners to perform on their own without needing to go through a practice activity. |

| Encourage on-the-job application and continuous learning | Provide opportunities and resources for learners to apply their new skills or advance their learning. For example, Dr. Will Thalheimer recommends providing an action plan mechanism where individuals can decide how and when to apply their new skills on the job. |

The WDF-DC approach is based on decades of instructional design research, especially the problem-centered instruction model from Dr. M. David Merrill and his book “First Principles of Instruction” (2020).

An example course outline

Based on the four WDF-DC instructional events, Table 2 is a high-level outline for a fictitious digital course titled “Patching your Operating Systems”.

Table 2. Outline for fictitious digital course

| Lesson | Example course outline |

| Introduction | The challenge The solution The benefits |

Task-based lessons: 1. Test patches | The worked example The guidelines |

| Practice activity | Introduce a new security breach challenge which requires patching a different operating system via a lab environment. The activity provides immediate feedback to help learners identify and fix their performance gaps. |

| Conclusion | Ask learners to identify an on-the-job project or future team meeting to apply or share their newly acquired operating system patching skills and knowledge. Also, provide a curated list of additional training or resources to help advance their learning. |

Levels of instruction

The primary strategy behind the WDF-DC approach is Dr. M. David Merrill’s levels of instruction. (Tables 3 and 4) Merrill argues that presenting information alone is not instruction. He suggests that the most basic level of instruction is showing the application of information to specific situations (i.e., worked examples). And the gold standard of instruction is when tasks are learned within a whole problem context.

Table 3. Course Components

Table 4. Levels of Instruction

| Course components | Levels of instruction | Importance |

| Present general Information without examples of how the information is applied. | Level 0: Tell | Presenting information alone is NOT instruction. |

| Show application of information to specific situations or tasks (worked examples). | Level 1: Show + Tell | Showing worked examples or step-by-step demonstrations is the most basic level of instruction. |

| Provide an opportunity to practice performing specific tasks and receiving feedback. | Level 2: Show + Tell + Do | Practicing and receiving personalized feedback on performance is how tangible skills are developed. |

| Introduce a relevant challenge, show an example of how to solve it, and then provide an opportunity to practice solving a similar challenge. | Level 3: Challenge > Show + Tell + Do | A single-threaded narrative or whole problem context is considered the gold standard of instruction. |

Merrill's levels of instruction align with the principles of situated cognition theory, indicating that knowledge acquisition is optimized when it occurs within its context. Similarly, situated learning theory emphasizes that learning is most effective when it happens in the context where it will be applied. (Scenario-Based Learning report, Massey University)

Indicators of good instruction

Merrill’s indicators of good instruction, yet another one of his many contributions to our field, help evaluate the success or lack of success of a training solution. (Figure 2 and Table 5)

Figure 2

Table 5: Indicators of Good Instruction

| Indicators | Description |

| Effective | Instruction is effective to the degree that the learner acquires the knowledge and develops the skills being taught. |

| Efficient | Instruction is efficient to the degree that this effectiveness is achieved in the least amount of instructional time necessary. |

| Motivating | Instruction is motivating when learners persist in their training and seek opportunities to apply their new skills. |

| Engaging | Instruction is engaging when it evokes positive emotions consistently across the learning experience. For example, a visually pleasing, accessible, and conversational design system helps increase the credibility of the digital course and its perceived ease of use. |

These indicators can be properly measured via performance-focused surveys, A/B tests, and on-the-job performance data. I conducted my own qualitative study (A/B test and post-training interviews) which helped further validate, refine, and optimize our design decisions. I am also happy to report that our WDF-DC-based courses consistently receive above-average learner satisfaction scores.

Furthermore, implementing an evidence-informed and scalable instructional design framework like WDF-DC enables the following benefits for your internal design and development groups.

- Clarifies the difference between well-designed (behavior-changing) and poor instructional design

- Helps improve client (stakeholders) trust and confidence in the design and development group and its methodologies

- Accelerates speed of development, maintenance cycles, and standardizations

- Helps identify targeted professional development opportunities for course designers and developers

Guidelines to keep in mind

The following are useful guidelines to help maximize the effectiveness of digital courses.

- Focus on a single behavior or skill. To create an effective learning experience, it is critical to focus on a single learning outcome or terminal behavior for your digital course. After defining this behavior, you can then work with your subject matter experts (SMEs) to define the enabling learning objectives such as processes, procedures, concepts, principles, and motivations required for performing the skill.

- Task-based versus topic-based approach. A topic-based approach is typically too generic, causes cognitive overload, creates motivational issues, and has a low probability of retention and transfer. On the other hand, a task-based approach can make the learning experience more meaningful and practical. For example, in a task-based approach the essential information (i.e., concepts, principles, and facts) relevant to the solution are presented in context of each task of the process.

- Beginner-to-advanced progression. Based on the prior knowledge of your target audience, you can create separate digital courses with the right set of challenges, worked examples, and practice activities that align with their levels of expertise. Further, you can build a coherent learning path that starts with a simple version of a challenge and then propose advanced courses with more complex variations of the same or a new set of challenges.

- Complex workflows. For complex workflows that take multiple days and involve multiple processes, you can create a short digital course that introduces the workflow and its processes at a high-level. After learning about the big picture and its parts, you can then provide separate deep dive courses for the different processes and tasks of the workflow.

- Keep your lessons short and concise. In instructional design, reducing cognitive load is paramount (less is more). This can be done by iteratively stripping away extraneous content that is not critical to achieving the terminal behavior. As a result, learners feel more confident and motivated to participate within their busy work schedules.

- Use short-form explainer videos. Short-form explainer videos explain concepts in a clear, concise, and engaging way. They can be fast to develop and maintain (e.g., Camtasia templates), while maximizing the processing capacity of working memory. According to the dual coding theory and Mayer’s modality principle, people learn more deeply from graphics and narration than from graphics and on-screen text.

Conclusion

Developing effective digital courses is hard and multi-faceted. It requires building strong stakeholder relationships, implementing research-backed instructional and visual design strategies, and being obsessed with improving the performance of your target audience. I hope you will find the WDF-DC approach a useful and impactful methodology for architecting your own digital courses. I am deeply appreciative of the work of M. David Merrill, Richard E. Mayer, Donald Clark, Jeroen J. G. van Merriënboer, Clark Quinn, Will Thalheimer, Patti Shank, Mirjam Neelen, Ruth Clark, Michael Allen, Connie Malamed, Julie Dirksen, Cathy Moore, Nick Shackleton-Jones, Christy Tucker, Bob Mosher, Con Gottfredson, and many others whose insights and guidance paved the way for my own performance improvement and instructional design learning journey.

In future articles, I hope to share additional well-designed frameworks for other instructional and performance improvement solutions, such as:

- Well-Designed Framework for Instructor-Led Training (WDF-ILT)

- Well-Designed Framework for Cohort-Based Training (WDF-CBT)

- Well-Designed Framework for Performance Support Solutions (WDF-PSS)

References

Merrill, M. David (2020). First Principles of Instruction, revised edition. AECT.

Ruth C. Clark and Richard E. Mayer (2016). e-Learning and the Science of Instruction: Proven Guidelines for Consumers and Designers of Multimedia Learning. Wiley.

Con Gottfredson and Bob Mosher (2010). Innovative Performance Support: Strategies and Practices for Learning in the Workflow (Business Skills and Development). McGraw Hill.

Patti O. Shank (2017). Practice and Feedback for Deeper Learning: 26 evidence-based and easy-to-apply tactics that promote deeper learning and application (Deep Learning). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Nick Shackleton-Jones (2023). How People Learn: A New Model of Learning and Cognition to Improve Performance and Education. Kogan.

Clark N. Quinn (2021). Learning Science for Instructional Designers: From Cognition to Application. Association for Talent Development.

Mirjam Neelen and Paul A. Kirschner. Evidence-Informed Learning Design: Creating Training to Improve Performance. Kogan.

Clark, Donald (2021). Learning Experience Design: How to Create Effective Learning that Works. Kogan.

Jeroen J. G. van Merriënboer (2017). Ten Steps to Complex Learning 3rd Edition. Routledge.

Michael W. Allen (2016). Michael Allen's Guide to e-Learning: Building Interactive, Fun, and Effective Learning Programs for Any Company. Wiley.

Julie Dirksen (2015). Design for How People Learn. New Riders.

Dana Gaines Robinson, James C. Robinson, Jack J. Phillips, and Patricia Pulliam Phillips (2015). Performance Consulting: A Strategic Process to Improve, Measure, and Sustain Organizational Results. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.